Lilli Waters

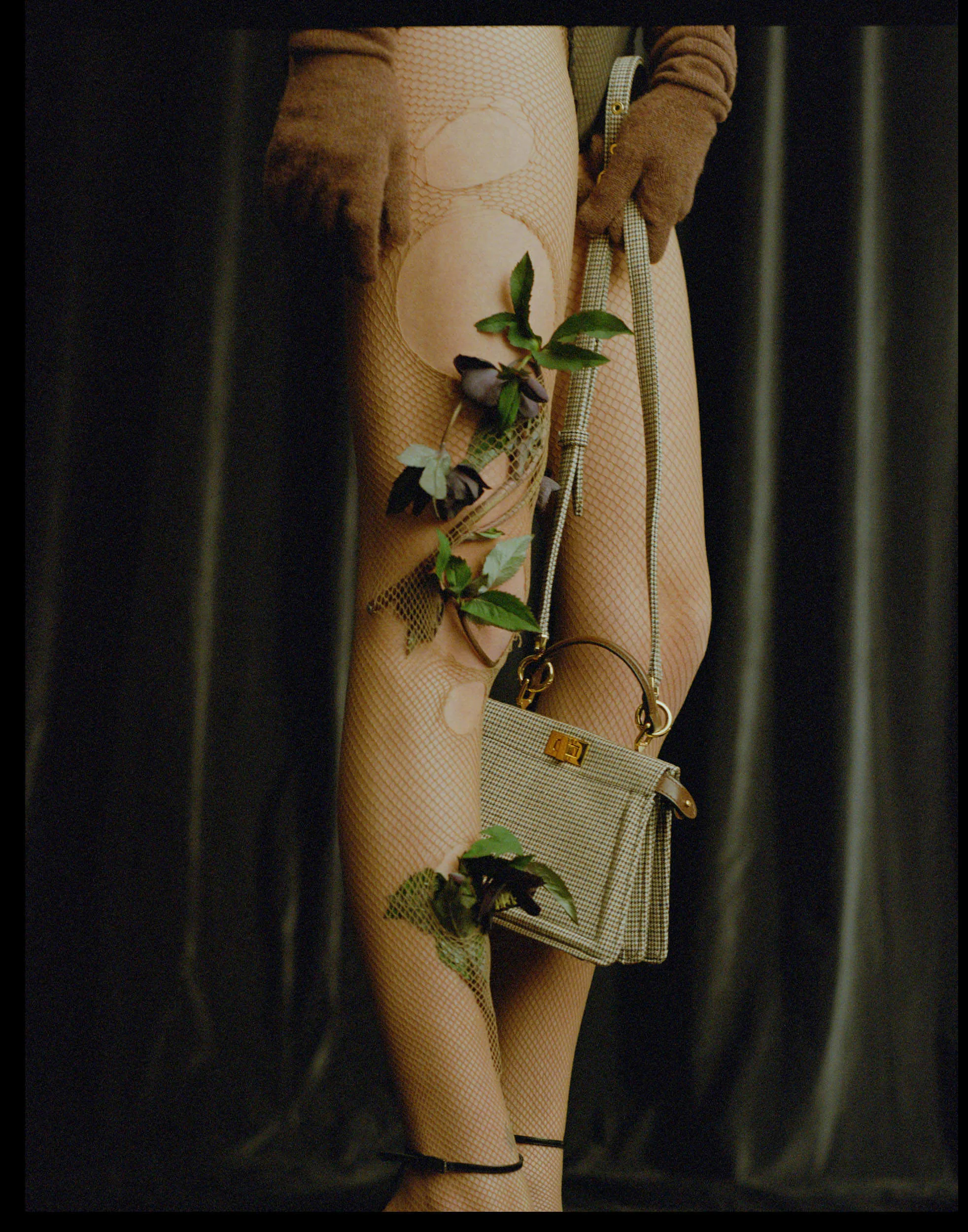

Lilli Waters creates images that catch your eye with considered stillness in motion and atmospheric depth. Drawing from her Thai-Australian heritage, as well as mythology and Dutch master traditions, her commercial and editorial work speaks to a growing appetite for visual culture that feels intentional, tactile, and emotionally present. In this conversation, Lilli discusses balancing meticulous craft with spontaneity on set, collaborative workflows that deliver memorable imagery under tight deadlines, and how thoughtful visual storytelling cuts through the noise.

When you look back, what really drew you to photography as the medium to express your perspective and the way you see the world?

I came to photography almost by accident. In high school, I was completely absorbed in making music videos, and pairing moving images with sound felt intuitive at that age. After a few of my clips received awards, I was invited to attend a small local photography school, the Photographic Imaging College. I enrolled because I wanted to study editing using the program Final Cut, but when the class was cancelled, I ended up spending a year in the darkroom instead, despite having barely taken a photograph before then.

In my second year, I made the misguided decision to skip the colour darkroom entirely and taught myself Photoshop on a clunky old G3. My printer teases me about this immature choice and insists that my lack of colour theory continues to reveal itself in my work, which is true. I spent many of the following years working as a retoucher, and it was not until much later that I left a horrible job and began to find any sense of personal voice or expression within photography itself. In many ways, I am still discovering what that voice is and what it wants to articulate, especially in a world that is increasingly oversaturated with imagery.

How has growing up as a Thai-Australian woman shaped the way you look at the world, and what you choose to capture in your photography?

Growing up, I never felt a strong connection to my Thai heritage. There were fragmented stories and dramatic rumours about my lineage and connections to the royal bloodline, but little link to the language, customs, or family. My connection existed only in fragments through old photographs from Thailand, the gestures of my mother and uncle, and memories of my grandmother and the traditional dress she brought back from Thailand.

It wasn’t until recently that I began exploring this heritage through my photography. In my upcoming solo exhibition, Sunken Water Gardens สวนใต้น้ำ, I delve into ancestral mythology and Buddhist cosmology, creating ethereal underwater still-life landscapes where plants, flowers, and fish become gestures linking the living with the divine.

Your upcoming solo exhibition Sunken Water Gardens สวนใต้น้ำ carries a Thai title alongside the English. Does สวนใต้น้ำ hold another layer of meaning or emotion that the English language doesn’t quite convey?

The Thai phrasing feels more like memory, something luminous. It hints at ancestry. Personally, it feels like a small connection point. The English describes, the Thai evokes.

You describe your connection to your Thai heritage as existing in fragments, in fabrics and family stories. What have you discovered about Thai mythology, culture, and traditions through the process of creating Sunken Water Gardens สวนใต้น้ำ that you hadn’t fully realised or understood before?

I realised how deeply Thai mythology had quietly shaped me long before I had the words to understand it. As I researched, I began to recognise symbols I had instinctively used, waterlilies, lotus, and water itself, as powerful spiritual motifs representing transformation and the meeting of worlds. Learning about the Traiphum cosmology, particularly the role of water as a threshold between realms, brought clarity to feelings I had long unconsciously carried and had been attempting to express in my work.

Your work appears to draw inspiration from still-life painting traditions, like the Dutch masters. What have you learned from the medium of painting, in terms of light, composition, or atmosphere? How do you translate those qualities in photographic form?

Artists like Rembrandt, Caravaggio, and the Dutch masters taught me to see light as emotion. They understood that stillness can be charged and that composition can spark a thrilling dopamine hit in the viewer. From them, I learned drama, the power of small shifts in shadow, the many spectrums of rich blacks that can exist within a photographic print, and the way colour emerges from darkness. In photography, I approach my sets as I would a painting, layering textures, arranging objects symbolically, and sculpting the light. Yet the medium introduces its own life. Flowers break, water moves, and fish dart around, so the photograph becomes a living still-life shaped by time as much as by intention.

Your photographs feel very considered and crafted, yet also alive and instinctive. How do you balance control and spontaneity on set, especially when you’re working with a lot of unpredictable elements?

I prepare meticulously, considering every plant, flower, object, fabric, and piece of fishing line, yet everything inevitably has a mind of its own. Water is always moving, with hands constantly adjusting the set. Flowers drift, fabrics bring their own choreography and colour casting, and I have to treat these disruptions as collaborators in this unfolding water ballet. Practising patience is tricky, waiting for the moment when the scene reveals something I could never have planned, or when it utterly fails, a ripple, a colour, a shape, a small accident. You have to be really honest with yourself and ask whether you have created something magical or if it is simply a mess that makes no sense. The success comes from trusting the set as a living ecosystem rather than a controlled stage. Many experiments end up being discarded, and the photographs that work often reveal themselves in post-production, where most of the work truly happens.

While your work is incredibly detailed and thoughtfully constructed, commercial photography and content production often move at a very fast pace. When deadlines are tight, what strategies or workflows help you maintain the level of detail and nuance your images are known for without compromising the final outcome?

Personal work and commercial work are very different worlds. In commercial settings, I am fortunate to work with wonderful teams, assistants, art directors, stylists, and set designers, and we collaborate closely. This structure allows for detailed pre-production, constructive feedback, and the exchange of ideas, which helps me maintain nuance and quality even under tight deadlines.

With my personal work, it is just me, so the process is slower, experimental, and highly intuitive. In commercial contexts, I translate that same attention to detail by planning in advance, breaking down each shot, and trusting the collaborative energy of the team. This allows me to work efficiently without compromising the depth and thoughtfulness I bring to the image.

When you step into a creative or art direction role on commercial projects, do you adapt your approach in any particular ways compared to how you work on your personal practice?

I shift from internal exploration to external translation. Personal work is guided by emotion and instinct, while commercial work is guided by clarity, brand values, and audience. I maintain my aesthetic sensibility, tactile and atmospheric, but I streamline it, focusing on communicating the essence rather than the personal. It is a different mode of working, but never a diluted one.

As a creative and art director, are there any tools, gear, or techniques that you find especially supportive of your process and workflow?

Constant lighting, skilled assistants, my little bag of tricks, and a love for Photoshop all help me shape a painterly, filmic atmosphere. I always enjoy incorporating nature and organic materials when possible, bringing tactility and a comforting presence into the frame. Working with creative collaborators who understand nuance is essential. The right set designer or stylist can make all the difference in bringing a vision to life.

We’re living in a moment where AI-generated images, fast content, and slop are everywhere. Being a creative person who crafts such tactile, human, intricate work, what role do you think photographers like you play in the future of building visual culture?

As Ethan Hawke says, “I am so bored by AI, I couldn’t be less interested in fake things. I like people, I like the way they smell, I like the way they talk, and I like the way they think. I like to think of AI as a plagiarising mechanism, that’s all it is. I know it’s going to change the world, it is screwing everybody up, and I am not in denial about that, but I am in open rebellion.”

I think we become custodians of emotional authenticity. AI can mimic aesthetics, but it cannot recreate lived experience, memory, humidity, grief, longing. Human-made images carry fingerprints, imperfection, presence, and vulnerability. Our role is to keep visual culture rooted in feeling, in physicality, and in the unrepeatable quality of real materials and real time. We remind the world that images can be offerings, not just outputs.

What role do you think your way of seeing and crafting could play in shaping more intentional, slower, or more emotionally resonant visuals?

I am hoping this new body of work invites viewers into stillness in a chaotic time, which feels increasingly radical. I want it to encourage people to linger, to sense atmosphere, to value symbolism, and to reconnect with the beauty of nature that is subtle rather than loud. At its heart, I hope my images can slow viewers down, even for a moment.

In a heartbreaking world, where wildlife, sea creatures, and the precious beauty of nature are being tragically and devastatingly lost every day on an almost unfathomable and irreversible scale at the hands of humans, I sense a deep, collective yearning for a renewed connection to the natural world. This is what I seek most.